Pretty Dendrites, Poorly Made

Implementing and Accelerating a Diffusion-Limited Aggregation Simulation

Introduction

Nature produces beautiful structures. Trees and rivers, snowflakes and frost, crystals and lightning bolts, to name a few. These structures form due to a mix of dynamic and energetic factors; the patterns depend both on how quickly it forms, and what patterns are inherently stable. I am no student of aesthetic philosophy, but I think that these structures are beautiful because of a mixture of symmetry and randomness. There is an incredible amount of detail with large scale structures.

To understand these systems, it is convenient to be able to reproduce some of these patterns. There are indeed models of these systems, some of which are amenable to relatively simple computational simulation. One is diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA). In DLA, a particle starts as a seed. Another particle moves randomly until it sticks to the stationary seed particle. Once it sticks, a new particle is generated far away and travels until it sticks to the growing cluster. However, to simulate larger and larger structures requires considerable amounts of computation — just because something is simple does not necessarily mean that it is easy to compute.

To explore a wide range of structures in a reasonable amount of time with my small computers, I need quick programs. With my academic engineering training, I have plenty of expertise with MATLAB. MATLAB, which stands for Matrix Laboratory, is a proprietary, interpreted (technically just-in-time compiled) language, designed for linear algebra problems. It is built upon fast FORTRAN and/or C math libraries (LAPACK and BLAS). So, linear algebra calculations and differential equations are simple, convenient and quick in MATLAB. However, a DLA simulation, with 1000s of particles checking the distance to each other every frame, would strain the MATLAB interpreter. I think I need to use a lower-level language to attain faster speeds.

The C-language is best for me and this situation. The main reasons were: (1) compiled to (possibly) fast programs; (2) plenty of online resources and tutorials on the basics; (3) chance to learn some of the foundations of computation and computer science. There are modern compiled alternatives that would probably give similar performance: e.g., Rust, Zig, Odin, etc. As far as I know, these solve problems I don’t care about yet (Rust’s borrow-checker and stricter memory safety), or are not yet into stable releases (Zig and Odin seem amazing, but are still new). And it nicely solves a personal problem. I am finishing my PhD and nearing the end of this chapter of my academic career. I cannot count on having a MATLAB license in the future. Thus, I am going to use C to make fast programs, generating beautiful structures.

In this work, and in what will become a series of posts, the diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) algorithm will be implemented. Structures will be rendered, described and analyzed. I will explain the quantitative analysis in a (hopefully) clear manner. Additionally, the code will be improved and lessons will be learned.

History: Diffusion and Simulations

Robert Brown saw it, so could you (Pearle 2010): microscopic particles in water or air move with random motion — called Brownian motion. Molecules surround the particle and randomly contact the particle surface, giving many little kicks. This contact randomly correlates to give a big kick. In fact, Einstein did the math on the “kinetic theory” of molecules to connect Brownian motion to molecular movement. (Einstein 1905), but that is another can of worms. Suffice to say, the motion of particles can be simulated by giving a particle a kick of a predetermined size in a random direction every simulation step. This algorithm is the base of basic diffusion simulations, including diffusion limited aggregation (DLA). It also provides a framework for analyzing the motion of the particles and the structure of the clusters.

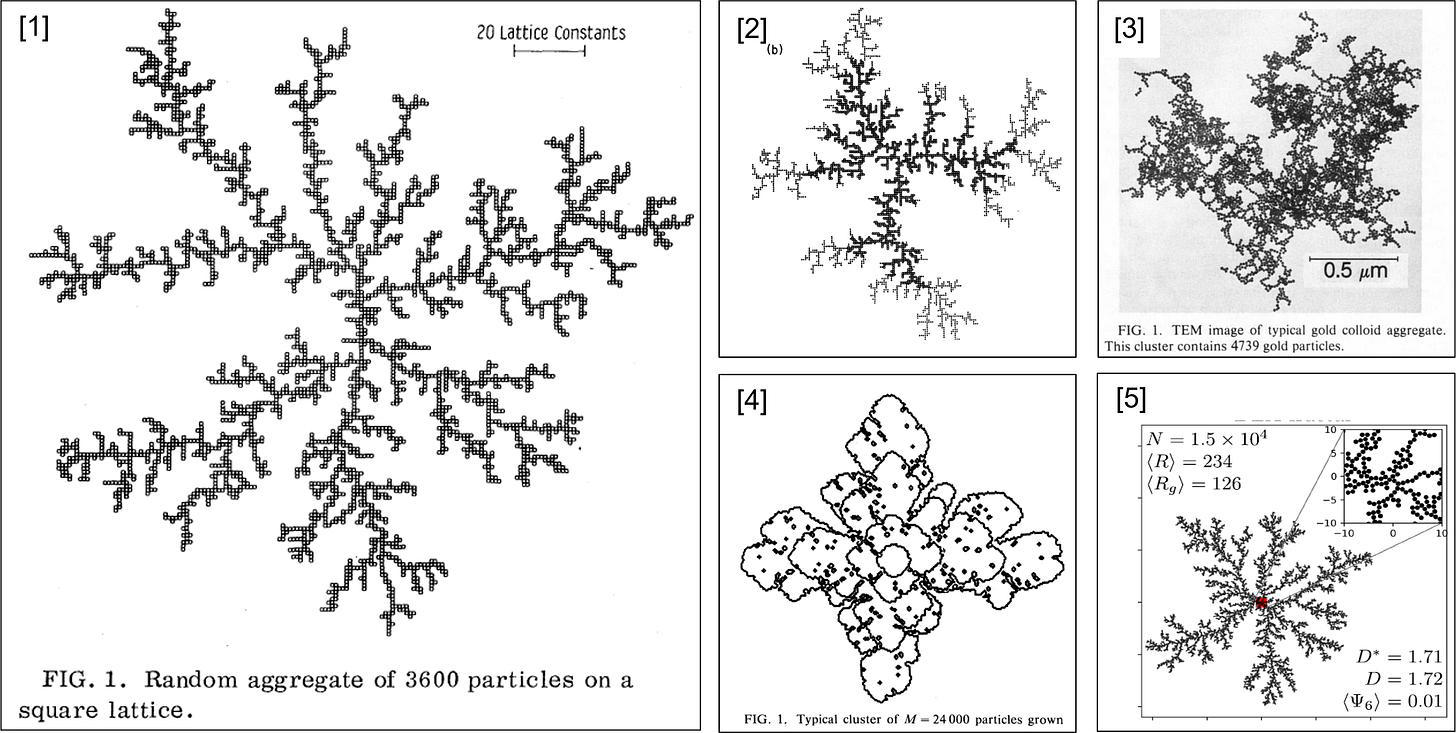

Witten and Sanders simulated it, so could you (Witten & Sanders 1981). By placing a seed particle at the center of the simulation, and allowing other particles to diffuse randomly, clusters form with fractal structure. One important feature of fractal structures is scale-invariance — if one zooms in or out, the structure has the same features — which was further confirmed by additional simulations (Witten & Sanders 1983). Scientists presumed that one could find real structures that follow these rules. Under a transmission-electron-microscope (TEM), a type of very high resolution microscopy, a pair of scientists found that gold nanoparticles formed clusters similar to DLA simulations (Weitz & Oliveria 1984).

Bigger simulations of systems with modified rules — from “particles always stick” to “particles stick with some structure-dependent probability” — yield additional structures, including snowflake-like patterns (Vicsek 1984). Skipping ahead in this non-comprehensive review, researchers are still studying these systems, including how the structure of particles influences the pattern of connections (Flores-Ortega et al 2023). The last paper is noteworthy as it describes both diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) and ballistic aggregation (BA) structures. Ballistic describes the type of motion not any connection to warfare — the particles generally fall towards the center, influencing the structure formed.

Basic Implementation

The pseudo-code for the code follows. There are some additional edge cases that require a more complex implementation, but this is the core of the simulations.

place particle 0 at (0,0)

for each particle i {

(x,y) = random point on circle of radius R

loop until broken {

add x = x ± step + bias(x)

add y = y ± step + bias(y)

for each other particle j != i {

if particle i touches particle j {

append (x,y) to list of stuck points

break do loop

}

}

}

}Note that that on every step, that x is incremented +step or -step randomly. This maintains an average motion that could be connected to longer time motion by Einstein’s theories. Now, bias in my implementation is a negligible factor that draws the particle towards the center. It scales with the particle position so that particles far from the center get a bigger kick towards the center, but it is always small compared to the step size.

As an initial run, 6000 particles were placed in the structure (Fig 2A). Due to the angular symmetry of the simulation, the particles form a roughly circular pattern. Thus, while the simulations were run in the xy-space, it is useful to describe the collection of particles with the radial distance from the central particle, denoted r. To get an idea of where the particles are, and to get some measurements of the structure, consider the number of particles in annular rings about the center, from r to r + Δr (red dashed lines and shaded region).

Binning all 6000 particles over 26 (how many I could run in sixteen hours overnight) simulations, there is a consistent pattern in the number of particles, N(r) (Fig 2B). Going away from the center, there are more and more particles, until it drops off. Of course, this is to be expected. There is more area for particles to occupy farther from the center of the annular rings. Consider the area of each ring,

For each bin, normalizing the count N(r), by the area A(r), yields the area concentration C(r). This quantity sheds more light on the local structure at each location (Fig 2C). Center effects mean that the central bins are dense (high C(r) at low r). This is likely an artifact due to small bins and few particles. At the middle, the concentration profile mostly levels off, with some rise with increasing radius. Then, once the distal end of the cluster is reached, C(r) tapers off.

These structural features seem promising for repeating simulations that show self-similar structures. One must not be too hasty. I ought to check a few series of simulations to check that these results made sense. If the simulations stop at different numbers of particles, we would expect different sizes of clusters.

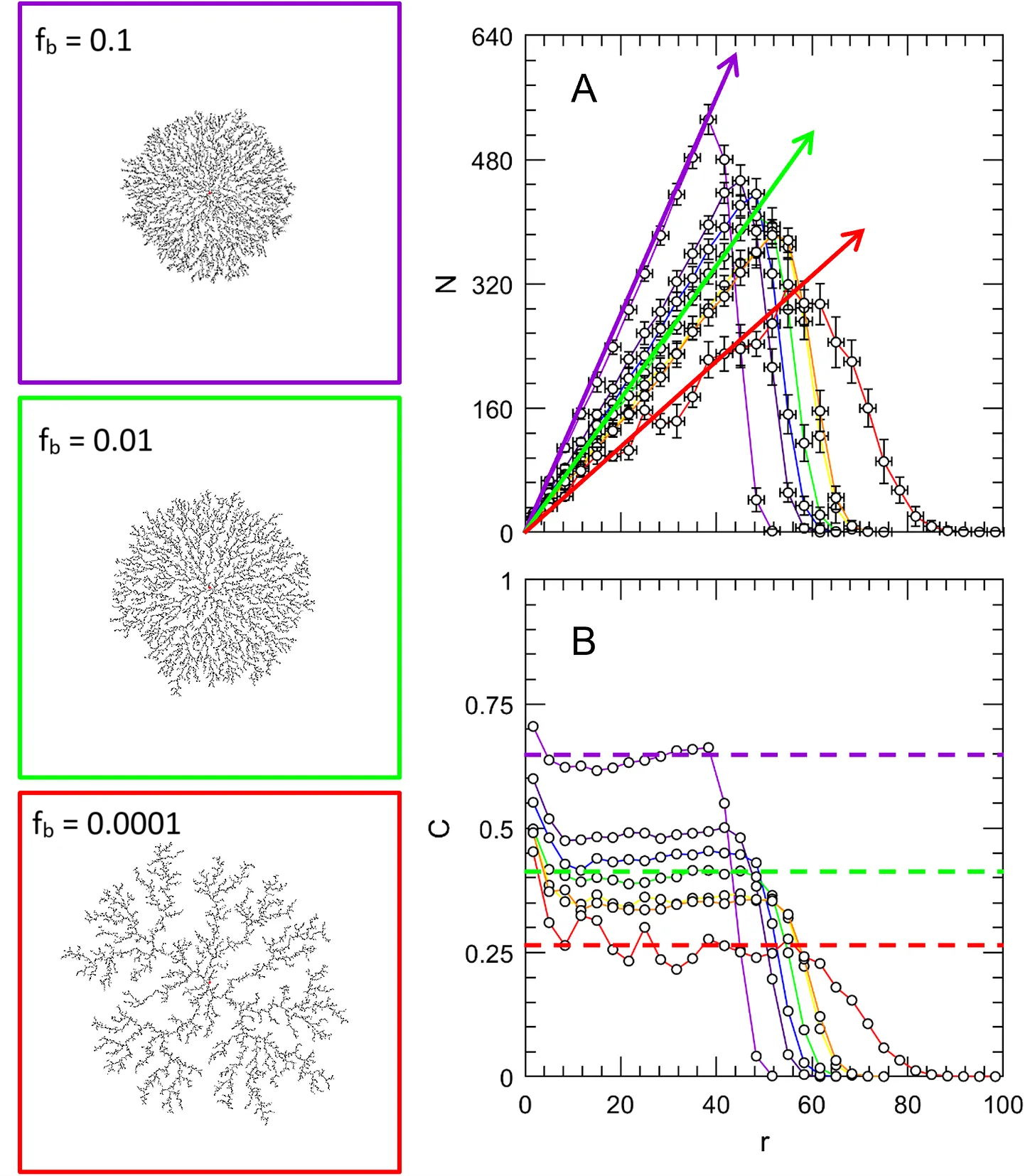

Different numbers of particles formed different sizes of clusters. As the number of particles increased, as did the size of the cluster (structures in Fig 3). Traversing multiple orders of magnitude from 100 (purple curves) to 10,000 (red curves), the clusters do not form different patterns. Instead, they self-similarly expand into the open space. For the smallest clusters, there is no middle region of the concentration (Fig 3A,B); center effects bleed into edge effects. However, for all the others, a consistent upward sloping middle concentration is seen. Further work on a system such as this could investigate whether the upward slope ever plateaus, or if it forms a dense, circular layer once a critical size is reached. Regardless, the simulations match with our expectations by growing with the number of particles self-similarly!

Numbers of particles exceeding 10,000 were taking too long for a just-for-fun project such as this. So, the bias factor was investigated, hypothesizing that different values might accelerate the simulations without affecting the patterns formed by the clusters.

The bias factor is gives a general tendency for particles to move towards the center. Generally, a particle moves every frame in the x-dimension, according to,

where Δx is the change in x, a is the particle size, fs and fb are the step size- and bias-size fractions. Thus, the step size is some fraction of the particle size, and the bias size is some fraction of the step size. It scales with the particle position, so that particles farther from the center will get a bigger push and no matter where the particle is, it will get a push towards the center. Steps in the y-direction were identical. My thought was to tip the scales in the favor of the cluster, in order to accelerate formation.

However, the clusters are qualitatively different for different bias factors (Fig 4 clusters). The green structure corresponds to the clusters of Fig 3. A higher degree of motion biasing makes the structures more dense (purple), and vice versa with lesser degrees (red). My biasing seems to concentrate the clusters, forming more or less spindly patterns.

The acceleration trick turns out to be more than just an acceleration. Instead, it fundamentally changes the patterns formed. Even the quantitative features of the patterns are different. There are many more particles close to the center of the cluster for higher degrees of bias (Fig 4A). And, the concentration of the middle section also shows bias-dependent effects (Fig 4B). I messed up! I suppose all the patterns are beautiful, but the fact that it was inadvertent raises questions.

Namely, what type of structures are these? They are not diffusion-limited aggregation structures, as they shouldn’t depend or contain any forcing function. Turns out, any tendency to fall to the center forms some nature of ballistic aggregation (Flores-Ortega et al 2023). I should have read these papers closer before trying my own thing! I have other ideas in progress for accelerating the simulations (mostly from the papers referenced here).

Secondly, are there better ways to generate these structures? The bias method was something that introduced additional dynamics, but it does not connect very well with fundamental theories of Brownian motion and cluster aggregation. And, if it is made with more rigor, a new direction on this tack is possible: instead of motion directly inward, spiral patterns might be able to be formed.

References

Note, my least favorite thing in writing is properly formatting citations. I will do my best, but it will end up a inconsistent mess of different citation styles. There will be enough to uniquely identify the source, mainly by the Digital Object Identifier (DOI).

Philip Pearle, Kenneth Bart, David Bilderback, Brian Collett, Dara Newman, Scott Samuels. “What Brown saw and you can too.” Am. J. Phys. 78, 1278–1289 (2010) (DOI) (ArXiv DOI)

Witten, Sander. “Diffusion-Limited Aggregation. A Critical Kinetic Phenomena." Phys. Rev. Lett., 1981. (DOI)

Witten & Sander, “Diffusion-Limited Aggregation.” Phys. Rev. B. 1983 (DOI)

Weitz & Oliveria, “Fractal Structures Formed by Aggregation of Aqueous Gold Colloids.” Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984 (DOI)

Vicsek, “Pattern Formation in Diffusion-Limited Aggregation.” Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984 (DOI)

Flores‑Ortega et al. “Network efficiency of spatial systems with fractal morphology: a geometric graphs approach.” Sci. Reports, 2023 (DOI)